GROUND CONTROL

Film: HD, colour, stereo, 13’, 1999-2009

Short description:

Film: HD, colour, stereo, 13’, 1999-2009

Director/ Producer/ Editor: Adnan Softić

Camera: Lilly Thalgott

Cast: Adnan Softić, Esma Softić, Sulejman Softić, Frank Henne

Colourist: Susi Montgomery

FX: Stefan Moog

Short description:

“At first Softić places the viewer in the situation of an external observer who seemingly has a function to fulfil in a medial act of vengeance. Then the notion arises that nothing in this film is as it seems. Adnan Softić’s video work "Ground Control" (Germany 2009) is a filmic reflection on manipulation and authenticity in film.”

3SAT

Out of Control

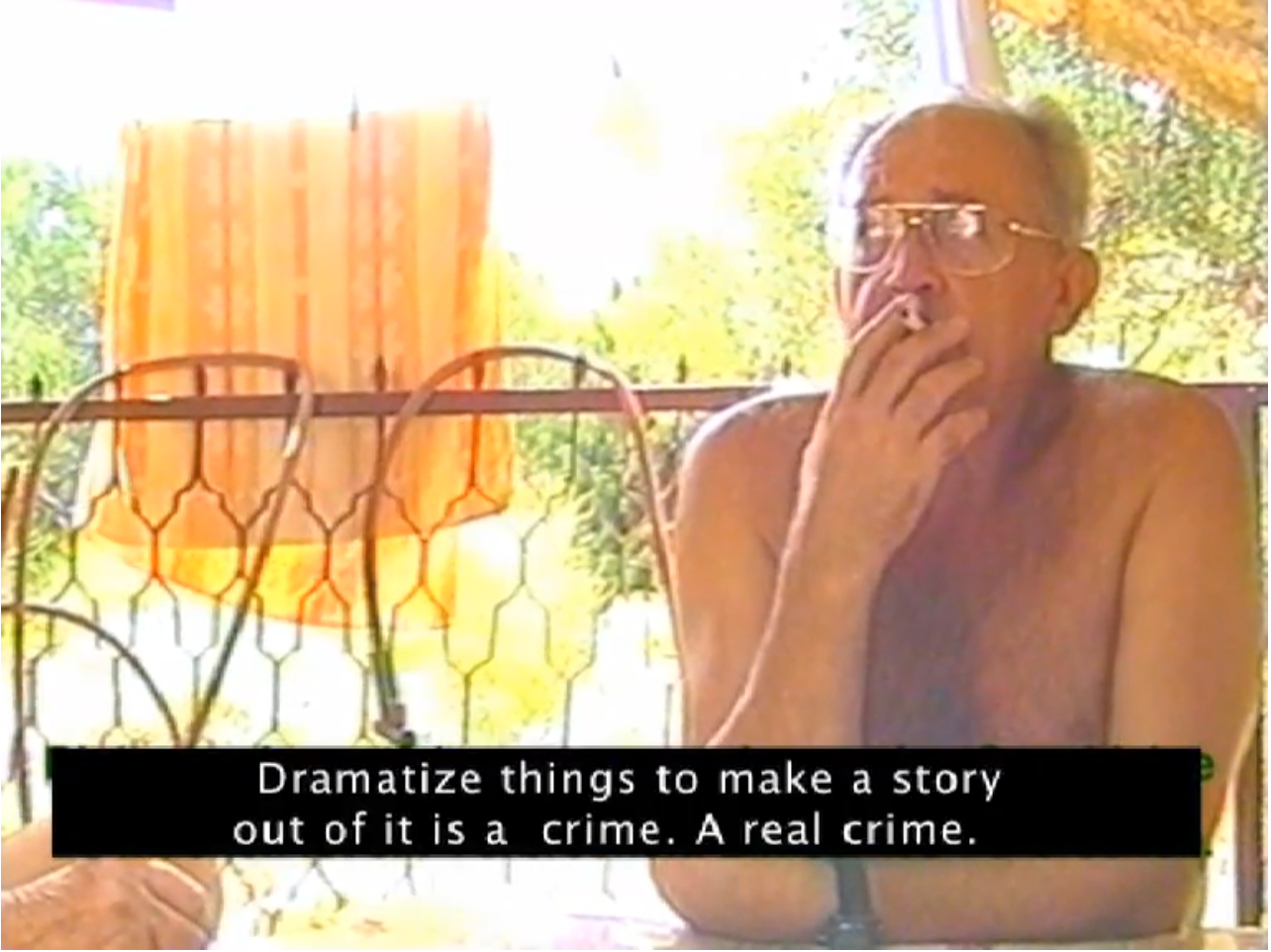

It begins harmlessly. An elderly married couple on the veranda of a shell of a bungalow still under construction – the scene is dominated by the tristesse of a holiday home complex. ‘He’, dressed only in bathing trunks, is reading a magazine, while ‘she’, rather more diligent than he, in once scene plucks leaves from a plant on the balcony or and in another scene does a crossword puzzle or busies herself in the kitchen. Incidental activities that allow the predominant order of the sexes to become visible: When a piece of washing threatens to fall from the line onto his head, ‘she’ jumps up to hang it again properly.

In a parallel action that accompanies these altogether everyday images we see a young man seated in front of a computer being asked by an interviewer: “What was his profession?”. In the cross-cutting of pictures and language a discontinuity of place and time manifests: Recreation and work, Bosnia and Germany. We discover that the person is being questioned about his father. He, the son, who at some point in the course of the film appears in short intermediate parallel actions on the veranda and reports, far away from the scene he is describing, in a fragmentary manner on the alleged past of his father, supposedly an ex-judge, explains his culpable involvement in the unlawful conviction of Islamic writers at the beginning of the eighties. These were manipulated court cases, conducted back then in Sarajevo with the purpose of cleansing the country of the enemy within. As a response to the interviewer’s question the son explains that the incriminating literature was in fact peaceful literature. The court cases served no other purpose than to systematically repress the truth. Yet the truth he tells us about is in turn only cited. This came to light, as the son admits, through the media. Since then, the father has been considered a persona non grata. The former enemies had taken on the position of power and the newspapers denounced the father, at times rather excessively, as being the real dregs. Why did the father participate? The son is convinced that this was not due to ideological motifs but completely materialistic ones. This was also the reason why his mother, who knew about the whole thing right from the beginning, went along with it.

It is meanwhile 1999. A decade of civil war has divided socialist Yugoslavia into many small nation states. However it is not the ‘big’ story that is being told here, but a minor one, a story that one can easily imagine could have happened in exactly this way. “Ground Control” obviously intends to reflect on the period before the war and that also means: before the mass persecution and murder of Muslim Bosnians. It is the period following the death of Tito in which there is a foreboding of the tension between population groups that seem to differ from one another for ethnic and religious reasons. However it is not this explanatory model anchored in West European memory that we encounter again here. Instead, we discover that it was Bosnian Muslims themselves who sought to silence the seemingly radical forces in their own ranks – forces that supposedly had relations to Arab countries. This is reminiscent of the Islamphobia that characterizes the current political and media discourse.

This, and the way in which “Ground Control” – in a really exaggerated mimetic manner – reproduces the children-question-the-past-of-their-(grand)parents documentary genre, generates doubt regarding the unbroken nature of the film. Doubts that are also sowed on a formal level – for example when at the beginning a second film title is faded in: “So und so” (This way and that), or due to the fact that the film was cross-cut from two parts from an earlier or later date. This can be seen by the fact that the son, who in the second part of the film is sitting on the sofa reading a letter aloud, has visibly aged. Is it a letter that he has written himself or one that he has received? Perhaps this is not important in the light of its strangely inconsistent content, as this reflects rather on the form of the ‘narration’ and the generation of truth connected to this. At this point at the latest, it becomes evident that the documentation we have just seen is a possible story – a film within a film or better put: a film about a film that already exists. It is the details that shed doubt upon what the ‘son’ says about his ‘parents’, for example that he does not want to have anything more to do with them. We see a photo cube that shows a portrait of his parents. The camera pans out to show a ‘typical’ living room with a TV and a play corner for children. The supposed letter therefore comments on what we have just seen and in this case we can read it as private or public, as a real of fictive contemporary document. It provides a basis for an approach to a past that cannot be abstracted from the ‘objectivity’ of the story told. We begin to ask ourselves why the artist has chosen the ‘stereotypical‘ narration (oedipal triangle!) to portray the conflicting relationship between the parent and child, in order to create a parallel with political history: the son judges his parents – the same way that the father once judged the dissidents.

It is a story that could have taken place in a narrative form, one that – as the first sentence from “Ground Control” implies – also possesses an objectivity that goes beyond the ability “to invent something”. The dark horizontal forms in the picture signify the inevitable media filters through which the images, the contemporary witnesses, the portrayed documents and those that portray are made to speak or are silenced. At the end the question remains, together with Michel Foucault: Who is the author and who is the addressee. Who is it that speaks? Who is it that asks? Who is being spoken to?

With “Ground Control” Adnan Softić intentionally orchestrates a loss of control as the roles and images created prove to be contingent and interchangeable: As assembled particles of reality that cut holes in the representation of that which could be considered to be the reality of the (narrated) story – however without negating the manifestation of ‘objective’ history in the form in which it is told. In this ambivalent state, the possibility of developing a different approach to one’s own standpoint, which is necessary for the individual and collective processing of a social trauma that separates the generations. Only in this way is it possible, loosely based on Foucault, to weaken this judge’s power, which he gains through the presumed claim to truth. The fact that Softić sets the position of the father/mother and son in relationship to one another and the way that he does so, marks this power as one in which the accuser and the accused both play an equal part and which allows us, the viewers, to question our own ‘position’.

Sabeth Buchmann