LUK- ONION- ZWIEBEL

Film: Super 16mm, 60’, 2004

Film: Super 16mm, 60’, 2004

Script / Director / Producer: Adnan Softić

Edit: Sandra Trostel

Camera: Bettina Herzner

With: Yuri Englert, Ratko Danilović, Andre Santen,

Iris Minich...

Music: Günter Reznicek, Ratko Danilović,

Thies Mynther, Anton Bruhin

Sound Edit: Thies Mynther

Set design: Ilke Penzlien, Christine Ebeling

Costume design: Nina Galinec

Suported by: The University of Fine Arts, Hamburg

Short description:

A cleaner observes his associates without ever actually meeting them. His son fears a burglar who doesn't exist. Their common friend meets a reincarnation of Janis Joplin whom he tries to convince to return to the netherworld in a “reasonable manner”

„Why do the branches keep on growing after the root has disappeared?

Why don't the leaves dry, although they don't receive any juice?”

Slicing through the onion

1.

“The film is based on a true story, however it does not correspond to it completely.” What could be perceived as a 'disclaimer' in the end credits if one watched the film backwards can no longer be considered a purely legal passage when the end credits are placed where they are, at the end. At the end of a film that at the beginning indicates the fact - the second indication aside from the events themselves – that the names of the protagonists are identical to those of the actors.

I envisage Adnan Softić wanting to collect the ingredients for his film and suddenly discovering that everything he needs is already there. He experiences something similar to Yuri (Yuri Englert), a man in his mid twenties who wants to cook for his sister (Iris Minich) and makes a shopping list. However, the ingredients are already there and it is not until this moment that he has the sense of having been shopping. The temporal-narrative structure of the film is fragile. Time and action fall apart in layers.

2.

One minute could mean one minute or a whole human lifetime. Yet at the same time, the scene is set in a completely ‘normal’ world: normal – at least for the duration of the shoot in the filmmaker’s home. However it remains unclear whether or not the figures have ever actually arrived in this world. Their perception is interrupted. Initially it is separated from the life of the outsiders. On the other hand it is exposed to something that always returns. The schoolboy André (André Santen) is frightened by the vision of a burglar breaking into his house. His father, Ratko, never sets eyes on his work colleagues – as a cleaner he cleans their rooms by night – however for him they are very much alive. As the narrator, he follows the trail of those that are absent. As a reader of the signs he acknowledges the most fleeting references as testifying an action.

The film is in three languages. Perhaps it is the remains of a timeframe that is expressed here. In the German subtitle one reads the following about Lenin: “For some people it’s a joke. For others he was a hero and for yet another he is a trauma”. A Bosnian commentary can also be found: “An unscathed stag asks his hunter for forgiveness”. Scraps of language from another world that insistently appear yet are incomplete. It is their empty places that distressingly return, like the empty chairs in a photo of the past. We lack connections and continuity.

3.

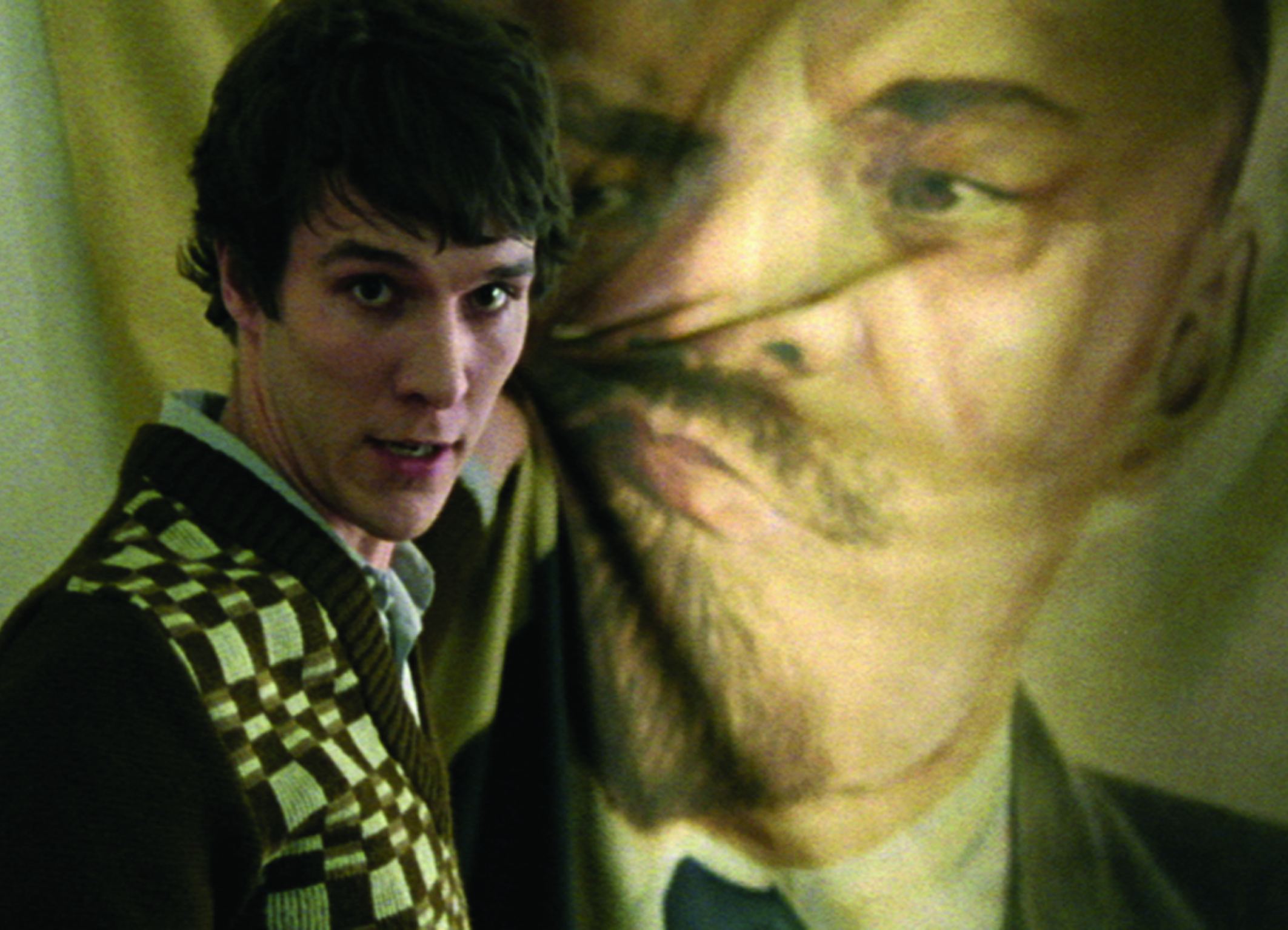

Luk - Onion - Zwiebel is a film that makes a philosophical statement. It is introduced by a facial composite drawer. A facial composite or phantom view can only be successful in connection with a criminal offence. The film asks: What could be a possible image of a phantom? While the artist working for the police advocates the obvious relationship between the crime and criminal, the film advocates a circular structure. It drifts and yet at the same time always remains in the same place. If one insists – together with the police officer – on the existence of an offender then this existence appears to be divided. It pervades people by interrupting connections. Yuri puts the phone down and says “bye” afterwards. A small hesitation that makes the farewell too late.

It is a rational onion that Yuri dissects right down to the core. Yet he finds nothing there. He finds nothing there but fear. Fear of the place in which instability turns into longing and from there once again into nothing. What may sound corny, in Softić’s film in fact conceals a moment of bizarre beauty. An apparition that defies any rationalization sings “Don't you cry!”. However emotional outburst and reason both deny any form of solution. They merely represent the point of transition: back into the unresolved cycle of interruptions, references and symbols. A phantom without the rigidity of the picture itself. This is possible in moving images.

Frank Wörler

Further descriptions

A cleaner observes his associates without ever actually meeting them. His son fears a burglar who doesn't exist. Their common friend meets a reincarnation of Janis Joplin whom he tries to convince to return to the netherworld in a reasonable manner.

This movie by Adnan Softić circles around questions regarding the perception of reality, hallucinations and projections of ideals. Already during the front credits of sorts the unstable relationship of unfiltered perception of reality, necessary protection against stimuli, and streams of association is addressed. As an episodic movie it is subdivided into three loosely intertwined narrative strands. One of them follows a pupil who is mostly encountered alone at home playing computer games and permanently feeling threatened by burglars; the second one shows a young man who likes to cook, conversing with his girlfriend and facing a further woman, whom he addresses as Janis Joplin; eventually he portrays an adult man, who earns his money as a cleaner, deducing the psyche of the people, whose leftovers he cleans away, from the atmosphere of the offices and the respective waste disposal management.

The three stories are not interconnected causally; their succession is additionally juggled by the repetition of surreal scenes. Occasionally the two men exchange their experiences; the younger man, so it is insinuated, could possibly be the cleaner's son - after all, they live in the same house. At the same time the movie expressly avoids conditional or causal narrative relationships, as it lets the individual episodes exist beside each other, and it evades determining the diegetic status of the images.

The intention is to evoke psychic realities. It affirms the fleeting transition between imagination and image, attacking the walls of figurative identification, and it explains that no original image is to be found on the inside of the onion. All images are deflections, deferments, as the author has the young man declare in front of a portrait of Lenin. Formally, the same status is bestowed on the image of him addressing the young woman with Janis Joplin as on the realistic scenes. Only the phantom draughtsman, unto whom the young man explains the physiognomies of the burglars he has seen, warns against the dangerous quality of imaginations, as they could effectively affect real people. Only under the impression of a shock would the image of an opponent be engraved beyond doubt in the witnesses mind in such a manner that it later can be reproduced flawlessly, lectures the phantom draughtsman. All other images remain subject to doubt with regard to their reproductive status – this is the source of the movie's specific humour.

Michaela Ott